Introduction

Building a video conferencing application like Zoom or Google Meet is one of the most challenging tasks in system design. It requires handling massive amounts of real-time data with minimal latency. To understand how these systems scale to support multiple users, we must look at the evolution of video architectures: from simple Peer-to-Peer (P2P) connections to advanced Selective Forwarding Units (SFU).

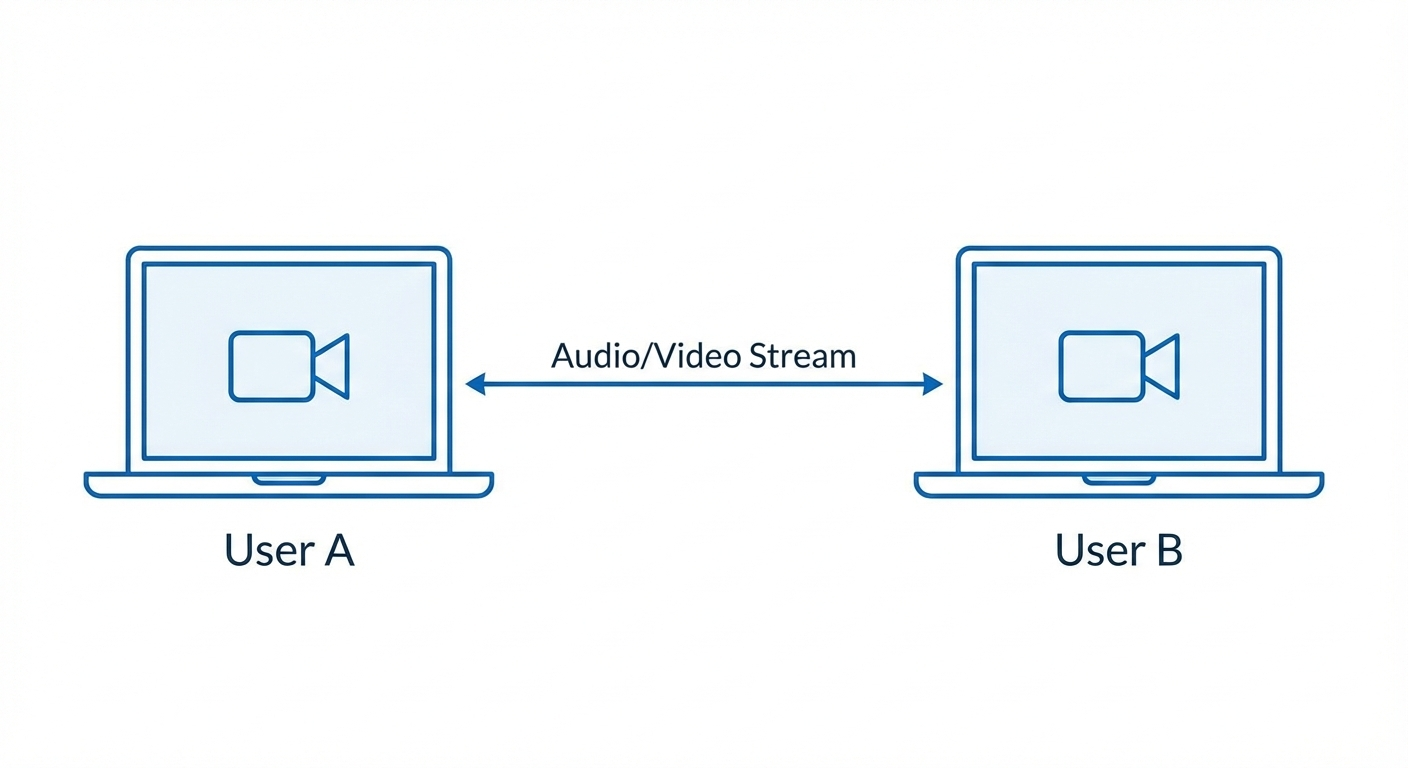

1. Peer-to-Peer (P2P) and WebRTC

The foundation of web-based video calling is WebRTC (Web Real-Time Communication). In its simplest form, it uses a P2P connection.

- How it works: Two users (peers) connect directly to each other using the UDP protocol. There is no central server handling the media; Peer A sends its stream directly to Peer B.

- Advantages: It is essentially "free" regarding server costs because the server only helps with the initial handshake (signaling).

- Limitations: This architecture is designed for 1-on-1 calls. Once you add more participants, it becomes a "Mesh" network.

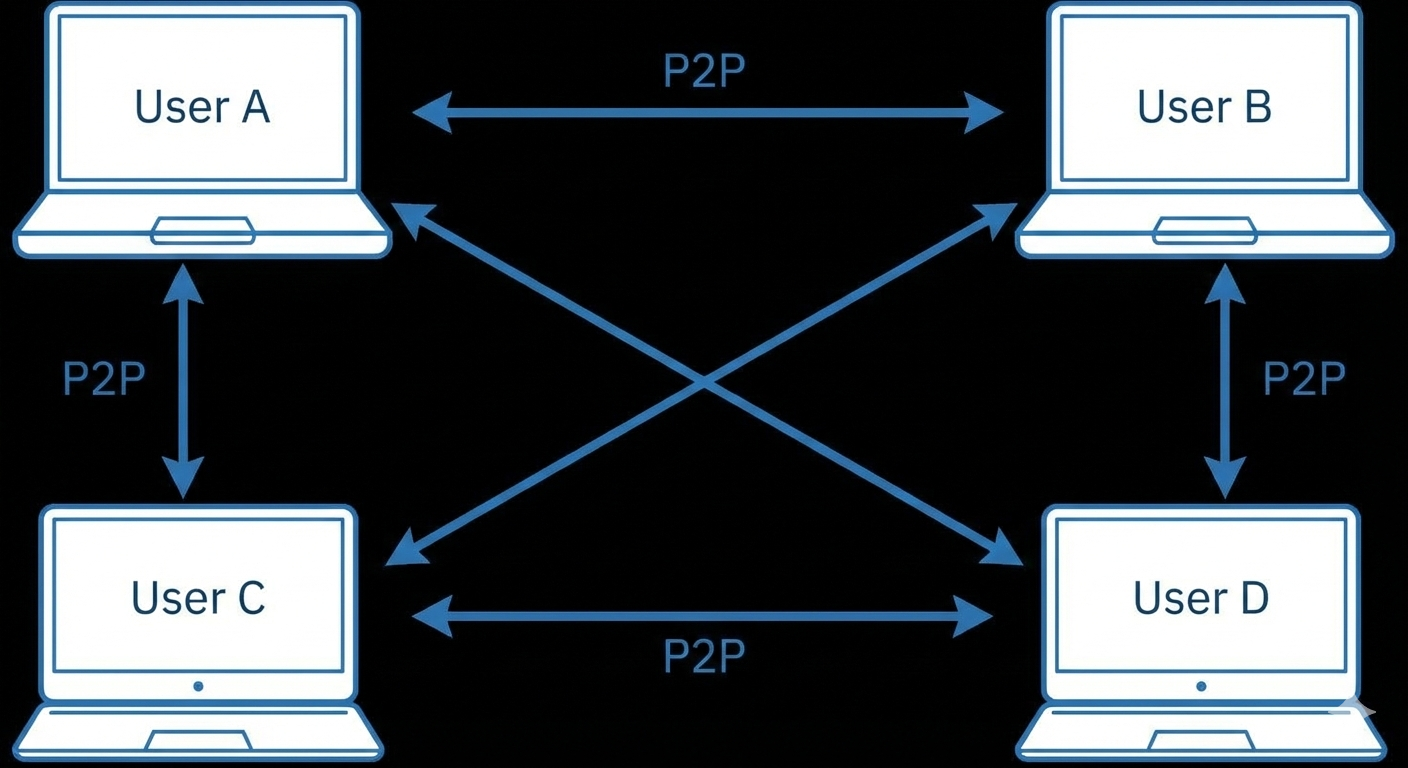

2. The Mesh Architecture

In a Mesh setup, every participant opens a direct P2P connection with every other participant.

- The Problem: If there are five people in a call, your device must upload your video four times and download four separate streams. This places an immense load on the user's CPU and upload bandwidth. It is not scalable for large groups and frequently crashes due to complexity.

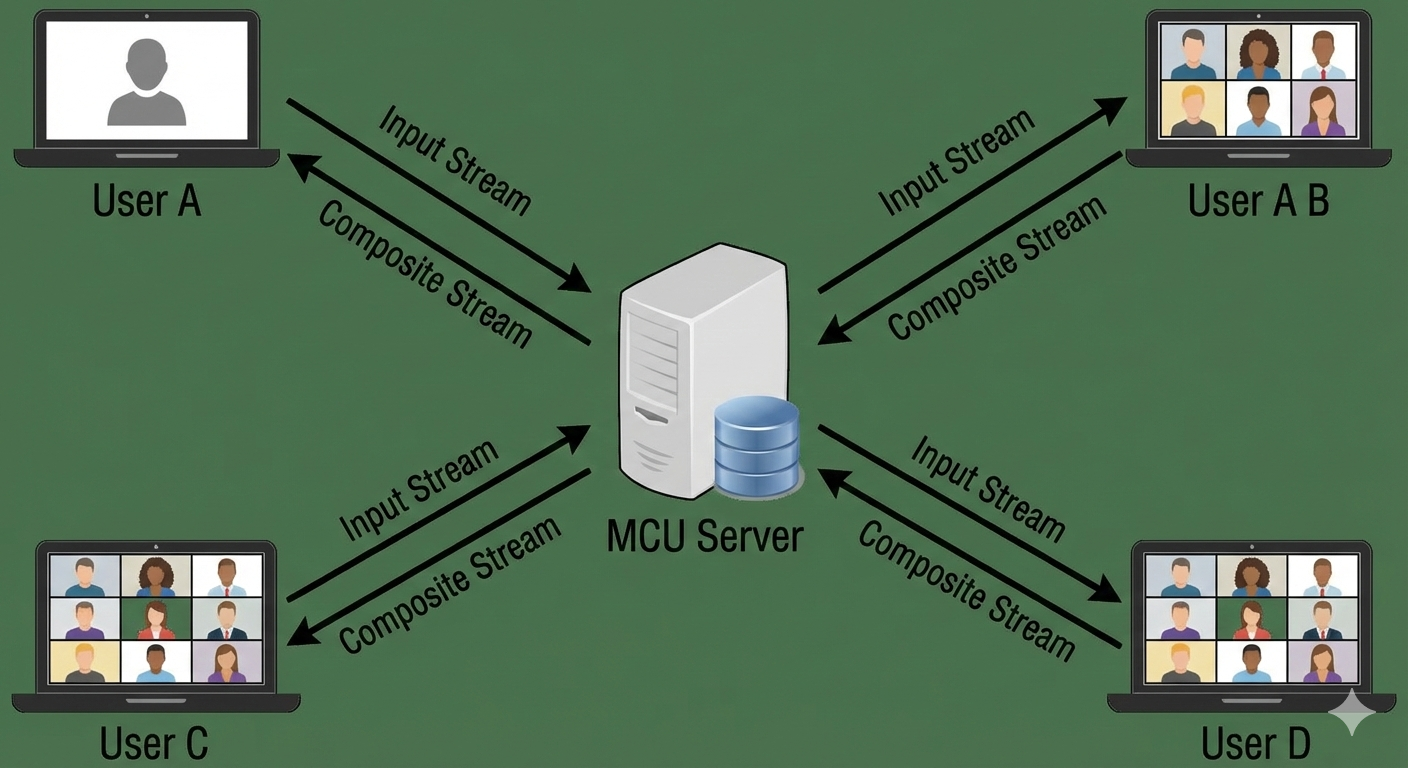

3. Multipoint Control Unit (MCU)

To solve the Mesh scaling issue, the industry introduced the MCU. This architecture introduces a central server that acts as a "mixer."

- How it works: Every participant sends one stream to the server. The server then takes all incoming video/audio feeds, "mixes" them into a single composite stream (like a collage), and sends that one stream back to everyone.

- Pros: Each user only handles one upload and one download stream, regardless of how many people are in the call.

- Cons: Mixing video in real-time is extremely CPU-intensive for the server. Furthermore, because the server sends a single "baked" image, users cannot customize their UI—you can't "pin" a specific person or hide someone locally because the layout is decided by the server.

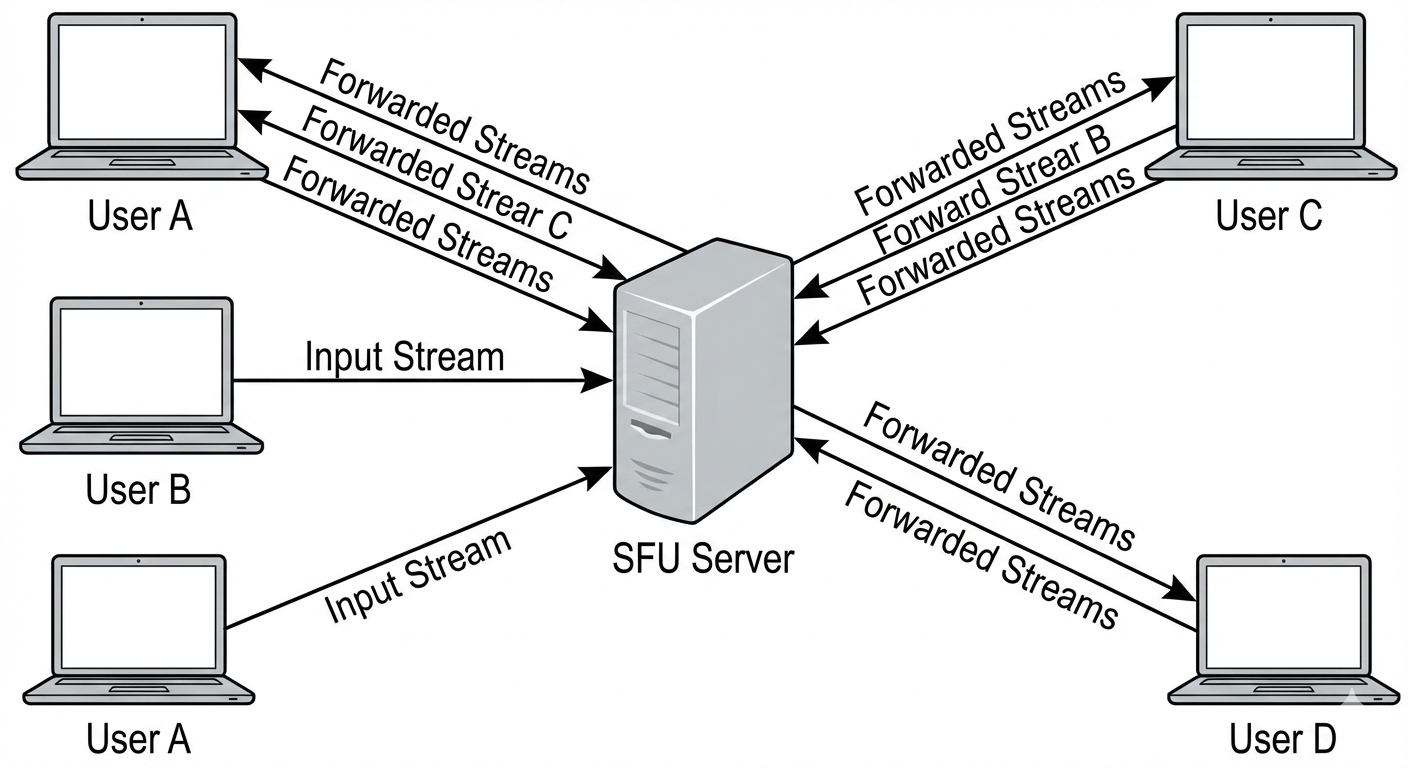

4. Selective Forwarding Unit (SFU)

The SFU is the modern gold standard used by most professional platforms.

- How it works: Like an MCU, everyone sends their stream to a central server. However, the SFU does not mix the streams. Instead, it acts as a "traffic cop" or a "router." It receives your stream and forwards it to the other participants as separate, raw feeds.

- Why it wins:

- Low Server Load: The server doesn't process or "mix" the video; it just routes packets, making it much cheaper and faster.

- Client Control: Since you receive separate streams for each participant, your app can decide how to render them. You can make one person's video larger, mute a specific person locally, or ignore a stream entirely to save data.

Conclusion

While P2P is excellent for simple 1-on-1 chats, production-grade applications requiring multi-conference capabilities almost always rely on SFU architecture. It offers the best balance of scalability, server efficiency, and client-side flexibility. For developers looking to implement this, low-level libraries like Mediasoup provide the necessary infrastructure to build robust, scalable selective forwarding units that can handle the demands of modern real-time communication